Clair Obscur: Expedition 33’s Ending Keeps it From Being Game of the Year

A near-impeccable experience marred by a third act that abandons the heart of its story.

Spoilers follow for the entirety of Clair Obscur: Expedition 33.

My initial thought after finishing Clair Obscur was that I wished I’d never played it. A strong reaction for sure, but I felt it captured the depth of my disappointment with the game’s ending. At the time, to have hours of genuinely great character writing and world-building end on a variation of “it was all a dream” felt like a massive waste of time.

That was six months ago, and in that six months the praise for the game has been nothing short of nonstop. While a lot of that could be from players who haven’t finished the game, it’s still unanimous enough for that little voice in the back of my mind to go, ”Shit, am I missing something?”

So here’s an attempt to answer that question. With the game recently taking home the big prize at The Game Awards, I figured this would be the perfect opportunity to interrogate my initial reaction and see if it truly stands up to scrutiny. Does Clair Obscur’s ending truly miss the landing hard enough to retroactively make the narrative worse? Or am I just unable to let go of a knee-jerk reaction?

Let’s start with the good.

What the Endings Do Well

That final decision to side with either Maelle or Verso is an insanely cinematic moment, and it’s a credit to the game’s writing that it’s a genuinely hard choice. I agonized for quite a while over who to choose, eventually opting for Maelle’s ending because of how much I cared for all of the painted characters. Saving Maelle’s mental health didn’t seem a convincing enough reason to wipe out an entire world and everyone in it (more on this later).

I did of course go back and pick Verso’s ending afterwards (and not only because Maelle’s ending left me a little cold). And as pure storytelling, Verso’s ending is very effective at putting us into Maelle’s shoes. While the complete eradication of the Canvas and all of its inhabitants threatens to make the entire journey feel pointless, there’s at least a consistency between the player’s experience and Maelle’s. We feel the despair that she feels. That same consistency is also what makes Acts 1 and 2 of the game work so well. The writing is great at getting us to feel what the characters feel.

And ultimately, I think that serves what the game is trying to do: get the player attached enough to this world and its painted characters that their loss is devastating. The result works as a comment on not just the power of the artist to make something transcendent, but the power of that art to stand on its own, independent of the artist’s will. This is especially true after the revelation that a piece of the real-life Verso’s soul is still in the Canvas. When painted Verso, a creation in that same Canvas, effectively destroys it, it makes literal the idea of an artist putting their soul into a work that then takes on a life of its own.

Maelle’s ending offers a different take on this idea, one where the audience manages to impose their will on the work. This is where Clair Obscur being a video game fits into the metaphor. Games are made by artists who impose rules on the player, but ultimately the player plays the game their way. This is especially true in JRPGs where a boss fight may be designed to force the player to use specific strategies, only for the player to surmount it through grinding and brute force instead. Certain games, like Final Fantasy XIII, curb this by putting temporary level caps on the player, but Clair Obscur’s mechanics revolve entirely around “breaking” the game. The various Pictos and skills you unlock tweak one mechanic or another to give you the feeling that you’re bending the game designers’ rules. This all goes hand-in-hand with Maelle’s ending where she rewrites the fabric of reality within the Canvas to create her ideal life, bringing back the people she’s lost.

What Doesn’t Work

You might have gathered this already, but a lot of what I found good about Clair Obscur’s ending works on a purely intellectual level, to the (in my opinion) detriment of the emotional function of the narrative. But this doesn’t start during the ending. Really, it’s the twist at the end of Act 2 that does it.

In general, I’m a big fan of twists that audibly make you go, “What the fuck?” And the ending of Act 2 has that in spades, as it’s slowly revealed that everything has been taking place inside a magical painting. On its own, I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with that twist. Like anything in writing, it’s all in how you handle it. But the danger with this kind of twist is that you take a story with very real stakes and essentially boil it down to “it was all a dream.”

To an extent, I think the game’s ending(s) fall into this trap. Especially Verso’s ending, which has the entire Canvas destroyed and Maelle forced back to her life in the real world, with the painted characters and Lumiere wiped out of existence. On a thematic level, we get an illustration of the power of art. But that’s something we already knew because, well, we were really into this game and affected by it. Emotionally, we’re left cold.

What really happens at the end of Act 2 is a reframing of what the story asks us to care about. Up until then we’re hammered with one million reasons why the Paintress must be stopped to save generations of Lumierians. It’s a life or death struggle for a people on the verge of extinction. After the twist, the focus shifts entirely away from the Lumierians to the Dessendre family, and specifically to Renoir’s struggle to free Maelle from the Canvas to force her to face her grief over the real-life Verso’s death.

It really can’t be overstated how much the Lumierians take a complete back seat to Maelle and Verso once the twist is revealed. Lune, Sciel, Monoco, Esquie, all the characters we’ve spent dozens of hours growing attached to no longer have a say in much of anything the party decides to do. And though I haven’t counted, it wouldn’t surprise me if they actually have drastically fewer lines of dialogue.

This is a problem because not only is the fate of the Dessendres a much less pressing set of stakes than the extinction of the Lumierians, the Dessendres themselves are much less sympathetic as characters than any of the Lumierians we’ve come to know by that point. The Lumierians sacrifice everything to save future generations. And the game offers Persona-esque Social Links to shed light on their pasts and the courage with which they face their respective traumas. The Dessendres on the other hand wipe out (seemingly) sentient life on a whim due to an inability to compromise or deal with their emotions in a healthy way. There really is no comparison in terms of who has the moral high ground.

For this reason, I suspect a lot of players initially chose Maelle’s ending when faced with the decision in the end. Because, truly, why care about whether the Dessendres deal with their grief properly?

And that’s where the narrative falters, because Maelle’s ending is very clearly signposted as a Bad Ending: the black-and-white filter, the eerie artificial veneer of happiness, the horror-movie-esque jump-scare shot of Maelle (complete with musical sting). Contrast this with Verso’s quietly bittersweet, slightly hopeful ending and it’s clear which outcome the game portrays as the better one.

Better for the Dessendres, that is. For every other character, the outcome is complete eradication.

But they’re just painted creations who aren’t real, so it’s fine, right?

Well, maybe? But likely probably not. And the key to proving that is actually Verso.

On Verso

I think Verso can help to answer a lot of questions. Because for as much as the story does not engage at all with the philosophical implications of its twist (specifically whether the painted people are sentient beings), the mere fact that painted Verso is able to force a human (Maelle) out of the Canvas is, in my opinion, proof that the painted characters have some degree of sentience or personhood, and aren’t just illusions following elaborate magical programming. They’re able to enact a will counter to that of their creators. Verso uses that will to destroy the Canvas and every painted character in it. In light of this, I’m left questioning why the game frames Verso and the Dessendres with the degree of sympathy that it does.

Sidenote: I’ve read a lot of takes claiming that the Dessendres aren’t meant to be portrayed sympathetically, merely realistically. I don’t think what’s in the game supports this idea. In Maelle’s ending, for example, you’re treated to an extended shot of Verso blubbering for death. It’s clear the cinematic intention here is to evoke some form of pity (i.e. sympathy). This is just one of many instances of this type of framing.

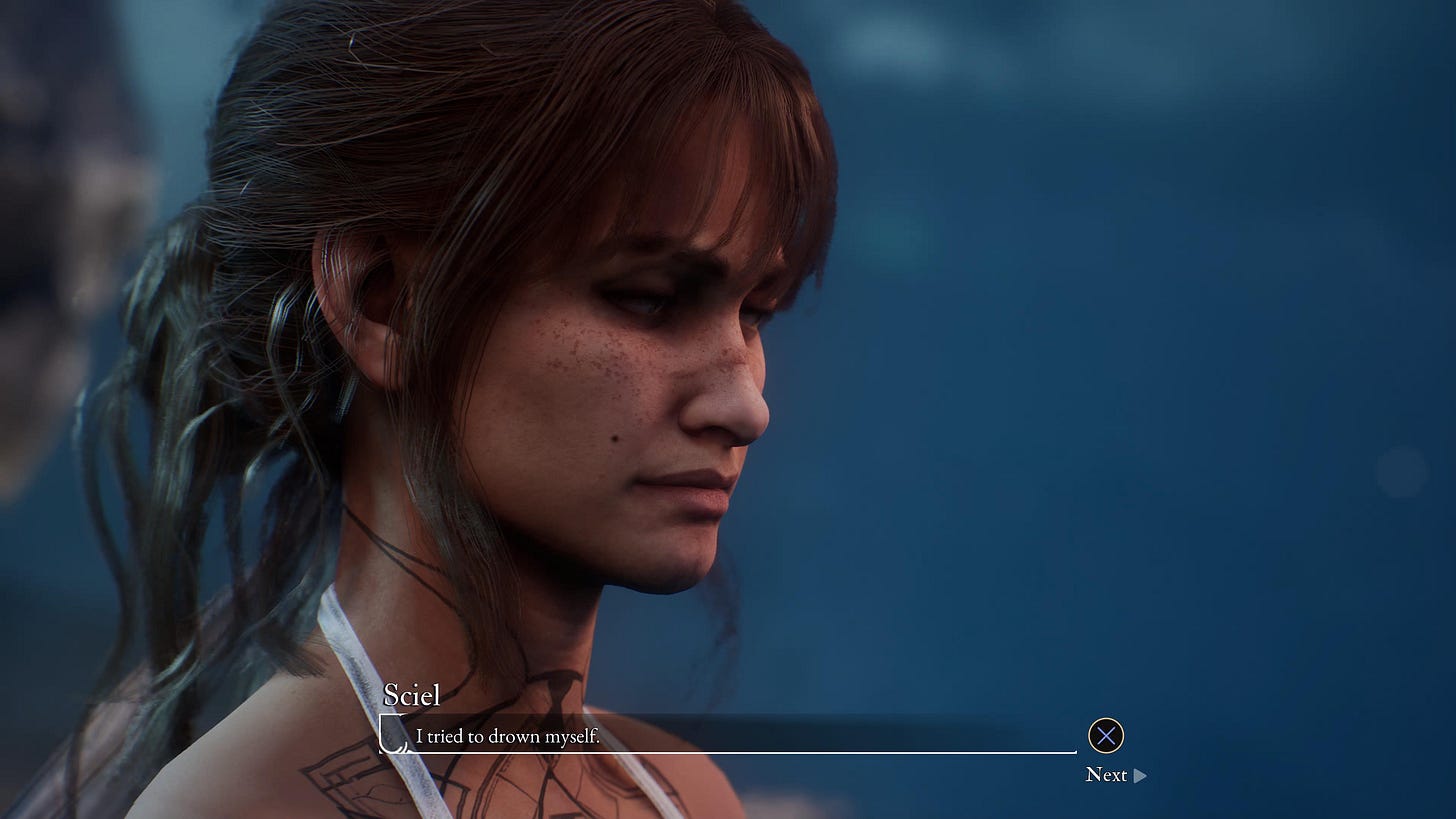

The sympathy feels unearned because the Dessendres commit some of the most evil acts imaginable. Renoir and Verso are responsible for the murder of entire generations, and Verso in particular can engage in some of the most insane behavior I’ve seen from a character in a game. For example, if you do Sciel’s Social Link (Persona has broken my brain and I have to call it a Social Link), you hear the devastating story of her suicide attempt and miscarriage, an attempt at connection that Verso reciprocates by sharing his own pain. Verso also has the option to make things romantic by sleeping with her. For all intents and purposes, they seem to form a deep bond.

However, if you do this and then pick Verso’s ending (which, remember, is framed as the better of the two endings), you apparently toss all of this aside and wipe her out along with every other inhabitant of the Canvas. It’s a sequence of events so baffling that it feels like an actual oversight. It honestly makes Verso seem like a genuine sociopath. And yet the game seems to prioritize the perspectives of him and the rest of the Dessendres, ostensibly because they’re “real” and the painted characters aren’t.

By not engaging with any of the philosophical implications of its twist, the ending the game leaves us with is, frankly, bafflingly tone deaf in its portrayal of the Dessendres and their grief. As soon as the twist is revealed, the painted characters are relegated to the background and effectively treated as disposable. Verso’s ending is portrayed as something sad, but ultimately necessary, as if saying:

“Sure, it’s sad that every single inhabitant of the Canvas was wiped out, but Maelle had to face her problems in real life, and the piece of Verso’s soul that maintained the Canvas deserved to rest in peace. After all, who amongst us hasn’t committed mass murder because a family member got too into one of their escapist fantasies?”

Game of the Year?

Clair Obscur does deserve praise. The writing, gameplay, art direction, music, every aspect of the game is firing on all cylinders. So I can understand why so many have this as their 2025 Game of the Year. But as good as all of those aspects are individually, they ultimately exist in service of the game’s emotional impact, and unfortunately the game doesn’t stick the landing in that regard. It doesn’t stick the landing to such an absurd degree that my immediate reaction was that I would rather have not played it. In hindsight, I’m glad I did. But that nagging feeling that the ending makes pointless an otherwise impeccable experience is hard to shake.

I think of the game’s opening: the quiet grief and poignancy of Gustave letting go of Sophie, the courage they faced their fates with, and compare it to the ending’s focus on the bottomless well of selfishness and stubbornness that is the Dessendres. Add that cynicism to a logical pretzel of a third-act twist and—even in a game otherwise as generationally good as this one—the ending can’t help but feel like a betrayal of everything that came before.